It can be said that: ‘Architecture is uniquely positioned to comment, advise and intervene in relation to questions about the role, form, aesthetic and provision of infrastructure. While architects are relatively powerless to provoke the changes necessary to generate renewed investment in infrastructure, they can begin to redirect their own imaginative and technical expertise towards the questions of infrastructure.’ (Tweeddale, 2012)

A definition of ‘infrastructure’ (in its rawest sense) can be found in Anna Tweeddale’s article: Infrastructure, Excess and Difference (2012) where she quotes the work of architect and theorist Stan Allen, who acknowledges that: ‘Infrastructural systems work like artificial ecologies in that they manage the flows of energy and resources on a site, and direct the density and distribution of a habitat. They create the conditions necessary to respond to incremental adjustments in resource availability, and modify the status of inhabitation in response to changing environmental conditions.’ (Tweeddale, 2012)

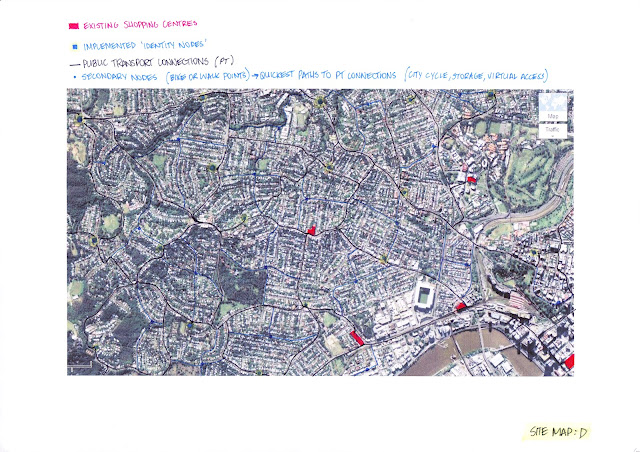

In contrast to this utopian definition of infrastructure, the heavily road-reliant plan prevalent nation-wide in Australia (and the US) represents ‘a US post-war urbanism, exported globally, that continues to promote the garden city and urban sprawl’ (Raggat, 2012). In Brisbane and greater Melbourne it has been used effectively to stimulate the economy at the expense however of turning productive farmland into unproductive suburbia, delaying the necessity of investing in public transport and spreading these cities ever thinner around the countryside.

There are moments where everyone can see that there is a paradigm shift needed with regard to the relationship of our natural and built environments. However, we are complacent and happy with the comfort level of certain things that we hope that the addition of more technology will solve these issues. Although this isn’t a method that can be applied to every urban situation, an example of the effective application of technology to provide a sustainable urban outcome can be found in South Korea’s capital Seoul and also its new city of New Songdo.

The article titled The Wired City by PD Smith in Architectural Review Magazine (August/September: issue 126) proposes that: ‘The world’s most wired and connected city is the South Korean capital of Seoul. Nearly every household in this modern high-rise city of 12 million people is linked to the cable network and can access the internet at a speedy 100 megabytes per second. The whole city has also been transformed into a wi-fi hotspot, thanks to an innovative wireless network that allows commuters on the subway to watch TV on their mobile phones. Those same commuters pay for their bus and taxi journeys with a radio frequency identification card.

Seoul is upgrading itself as an ‘open data city’ in a belief that an informed city is a more efficient city. Thanks to the ‘Ubiquitous Seoul’ (U-city) project, Seoul’s online citizens will be able to access real-time urban data from sensors around the city. New homes in Seoul are being designed with ‘Ubiquitous life’ (U-life) features, allowing them to be centrally controlled by a keypad or remotely with a smartphone.’ (Smith, 2012)

It can be seen from the above example that the effective overlay of an efficient virtual component is resulting in an informed, connected and sustainable city. The New Songdo project also aims to exhibit this same virtual component, however having been implemented at its inception and having had the luxury of being built from scratch, it can therefore more effectively accommodate this technological aspect.

Conversely, there is no reason for Australia or even Brisbane to build from the ‘ground-up’ like New Songdo is doing in this case. Not only is it unnecessary as we already have the framework in place that has the potential to sustainably support itself (it just hasn’t been realised yet), but because it would be a complete waste of little resources we have. By becoming less road-reliant and by living in more centralised, densified locations dispersed throughout SEQ, the implementation of a ‘Ubiquitous system’ as proposed by the Seoul project would not only hugely benefit the economy and socio-cultural urban fabric, but would also cease expansion into the natural environment. This would simultaneously ‘free up’ urban greenspace in the process and would result in the first steps being taken to the preservation and re-invigoration of the natural environment. This re-invigoration would in turn result in a socially, economically and environmentally sustainable community on a local, regional and national level.

References:

Tweeddale, A. (2012). Infrastructure, Excess and Difference. From Architectural Review Asia Pacific Magazine. Issue: 126 (August/September, 2012). Published by Niche Media Pty Ltd:Melbourne.

Raggat, M. (2012). Melbourne Gateway: Oblique Architecture. From Architectural Review Asia Pacific Magazine. Issue: 126 (August/September, 2012). Published by Niche Media Pty Ltd:Melbourne.

Smith, PD. (2012) The Wired City. From Architectural Review Asia Pacific Magazine. Issue: 126 (August/September, 2012). Published by Niche Media Pty Ltd:Melbourne.